Geospatial Technology: Visualizing, Predicting, and Reacting to Large-Scale Disasters

As complex spatial data and GIS have grown more and more ubiquitous, so too has the public’s ability to better comprehend events happening time zones away from them. Likewise, the rise of such technology has also improved people’s ability to react when disasters strike close to home.

In August, a deadly explosion in Beirut captured the attention of the globe. Footage of the event spread rapidly over social media, but for many, understanding the magnitude of a blast in a city they have never visited was made possible with diverse visualizations like those in a New York Times article. In one image, circles representing the blast radius are overlaid on top population density data. In another, satellite imagery of the city is overlaid with data points like kinds of damage reported (from leveled buildings close to the explosion to blown-out windows miles away from its center) and other information specific to individual neighborhoods.

Image courtesy of the New York Post.

Other large-scale natural disasters, like wildfires, hurricanes, floods, landslides, and air pollution, are often difficult for individuals to truly comprehend but also necessary to react to, in both the immediate and long-term. GIS allows multiple forms of data to overlap and paint a clear picture of both the physical and socio-economic impacts of a disaster.

In the United States, the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Hurricane Incident Journal keeps tabs on both the severity of an approaching storm and how much potential harm already-disadvantaged populations may face. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) data projecting the path of storms is conflated with data from the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index. For 2020’s Hurricane Laura, COVID-19 case data from Johns Hopkins University was also added to that mix. The United States Army Corp of Engineers’ Flood Inundation Mapping project provides an interactive map with levels of information from stream gauges and levee information to help predict where floods may strike afterward.

Image courtesy of WDSU News.

Similar tools exist for tracking wildfires, like those currently ravaging the west coast of the US. The United States Geological Survey’s (USGS) Landfire Data Distribution Site tracks fires in real-time, as do several other non-state organizations. Advances in unmanned air vehicles and the Internet of Things have allowed for more rapid updates with less risk to humans.

Recently, Google has added data to ensure that these kinds of apps can continue to be frequently updated and rapidly accessed, meaning the tools stay useable even as demand for them increases with the advent of a disaster.

After fires burn through the vegetation that, quite literally, holds land together, landslides are a common occurrence. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) has tools to monitor those threats in real-time, including landslide monitoring and post-fire debris flows, and informational guides for understanding the maps. The USGS also provides similar tools for earthquakes. This data is created in cooperation with institutions like the Colorado School of Mines.

Image courtesy of The San Francisco Chronicle.

Of course, since this is spatial data, there are non-governmental actors providing knowledge as well. One example is PurpleAir, an air quality tracking site created using the Internet of Things, including devices you can buy on-site to monitor air around your home and contribute to the overall data. For a non-governmental live look at developing storms, Esri’s disaster response hub houses a wealth of tools.

Geospatial data continues to play a crucial role in not only tracking & responding to a natural disaster but also informing the public on the gravity of the situation. The tools and visualizations made available by geospatial data and GIS software continue to provide key insights and information for decision-makers and laypeople alike.

The Role of Physical Maps in the Digital Age

Enhanced digital capabilities have revolutionized the world of maps for consumers and professionals alike. As noted in one of our previous posts, digital maps allow cartography to leave its 2-D boundaries in the past. They also allow for rapid updates and infinite customization. There are, however, several things digital maps cannot do that paper maps can – enough to make any claims about paper maps’ days being numbered ring hollow.

The biggest advantage paper maps still hold is reliability. Digital mapping tools require multiple, complex technological systems to maintain steady coordination for data to be accessible. Though relatively infrequent, threats like power outages, solar flares, or even a squirrel on a power line can interrupt these systems. A government shutdown could hamper satellite data powering GPS systems for both consumers and companies. A paper map, once created, exists until physically destroyed; all one needs is light to read it by.

This ‘feature’ comes in handy when navigating remote places of the world with tenuous (or non-existent) internet connections and sparse existing GPS data.

But what about the information on that map? Couldn’t it be outdated? The short answer is yes, but the same can be said for many digital maps as well. When accessing data digitally, like on Google Maps or Waze, there is an expectation that the map has been updated recently. Online mapping services, especially those free to consumers, are somewhat opaque about when they were last updated, though, and some applications, like OSM (Open Street Map), rely on crowd-sourced data. Intentionally or not, this data could be bad or misleading. Physical maps are transparent about when they were published and what they cover. This makes it easier to identify gaps in knowledge ahead of time.

Plus, with a little bit of pre-planning, today’s trend of print-on-demand maps makes it easier than ever to get the most accurate information into your hands, literally.

In fact, even as today’s ships and airplanes use digital data to navigate the air and seas, paper aeronautical and hydrographic charts are required by law as a backup. Entities in other industries, like sales and telecommunications, also keep sets of physical maps handy to ensure that their efforts will not grind to a halt due to interrupted digital data. Today’s print-on-demand capabilities mean these backup maps can be just as specific as their digital counterparts.

East View Geospatial has helped create and supply physical maps for sales teams and telecommunications projects in the past and can create products for incredibly specific scenarios. Our work for the new Amazon Prime series, World’s Toughest Race: Eco-Challenge Fiji, hosted by survival legend Bear Grylls, is one example. For Eco-Challenge, we created 11 different maps for the staff and contestants and printed a total of 991 copies.

What the contestants do with those maps will showcase the biggest benefit of physical maps; increased cognitive ability.

Studies have shown that the use of paper maps can stimulate more in-depth thinking and a deeper level of situational awareness than using maps on a screen. A digital map app gives A-to-B directions, and users typically follow those directions. When a wrinkle or recalculation occurs, it can be jarring. The process of digesting information from a paper map is more of a holistic brain process that hones skills like orienteering and spatial awareness.

It’s easy to infer, then, that the meandering nature of travel is often best left to the old ways, since paper maps are easier to deviate from due to their ability to impart context to users.

Of course, some maps are simply too out-of-date, too battered, or too specific to be much more than a decoration. Or, even further, ‘mapping’ paper for presents. Before that kind of recycling, though, think about whether or not your navigational skills are becoming a victim of convenience.

Maps: Historical Inaccuracies That Shaped Perception

Whether due to honest mistakes, purposeful deceptions, or the inertia of progression, inaccurate maps have consequences.

In previous posts, we have detailed how maps and geospatial data shape the very fabric of reality around us, and we’ve also chronicled the advances in accuracy through the ages. But what happens when maps, or their users, are slow to catch up with the times? Early mapping was far from accurate, and parts, we now know, were based on superstition. In other cases, they were based on deception.

“The Phantom Atlas,” by Edward Brooke-Hitching includes examples of purposeful mapping falsehoods.

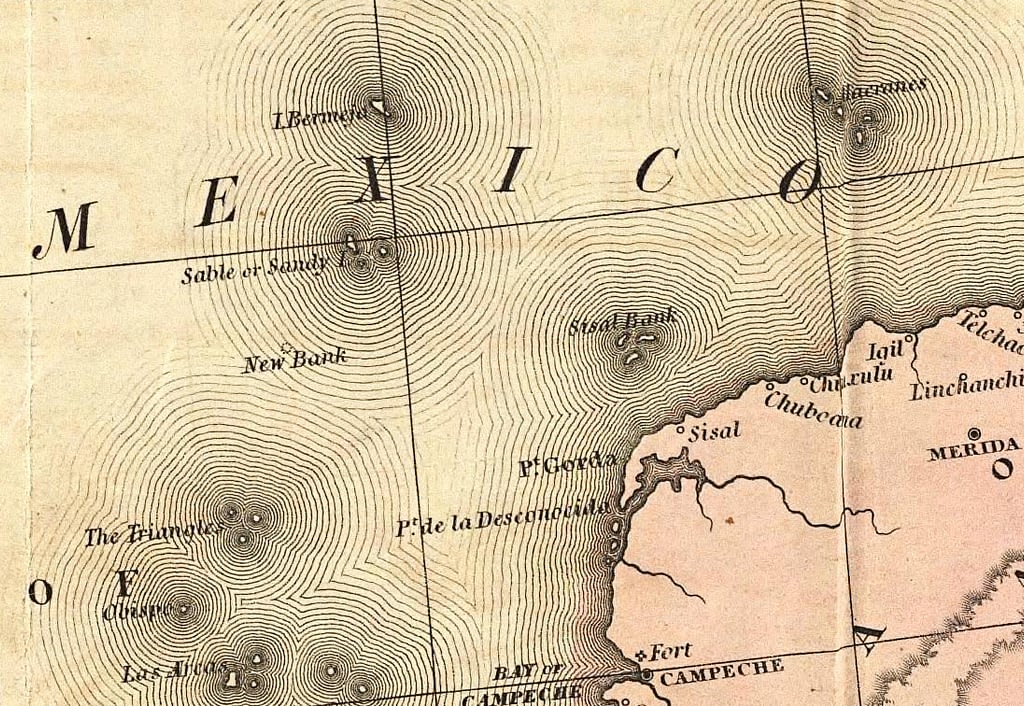

In 1539, the Mexican island of Bermeja first appeared on Spanish maps. It continued to appear well into the 20th century. Starting in the 1980s, the Mexican government hoped to find it and secure oil rights on the island. Searches for the island persisted until 2009 when it was concluded the island did not exist.

Bermeja as depicted on a Spanish map via the David Rumsey Map Collection.

Infamous deceivers like Benjamin Morrell, who ‘discovered’ islands like “New South Greenland” and “Morrell’s Land,” where only open water exists, took advantage of the public’s credulity. In 1822, Gregor MacGregor convinced 270 British colonists to sell their possessions and buy land from him in the newly-established South American country of ‘Poyais’. The problem was, MacGregor’s ‘Poyais’ land was nothing more than swampland; most of his settlers never made it back to Britain.

The trust people have in maps is significantly increased when children are the consumers. When a child sees a map of the world for the first time, it is presented as an absolute fact. In the case of older sea maps scattered with krakens and giants, children may grow up believing monsters roam the earth and seas. In the case of the standardization of the Mercator projection map, children grow up with distorted ideas about hemispheric proportions and global dynamics.

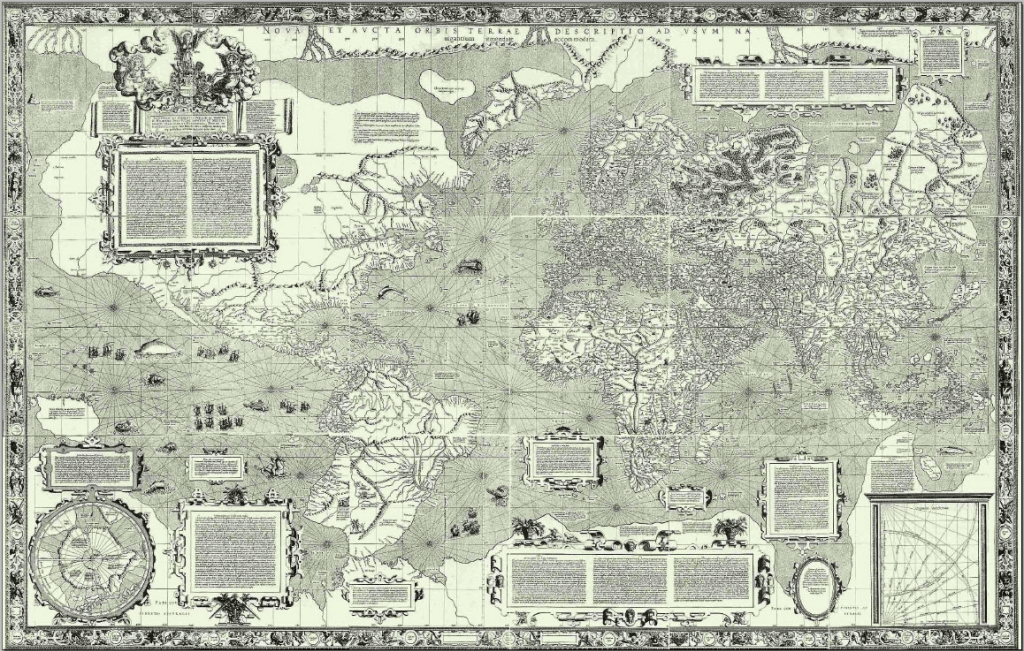

When Gerardus Mercator released his 1569 map, “A New and Enlarged Description of the Earth with Corrections for Use in Navigation,” he was not intending to introduce a standard visualization of the Earth. The map’s purpose was to allow straight lines to be drawn between ports and used as a practical tool by sailors, navigators, and travelers.

New and Enlarged Description of the Earth with Corrections for Use in Navigation Map via International Cartographic Association.

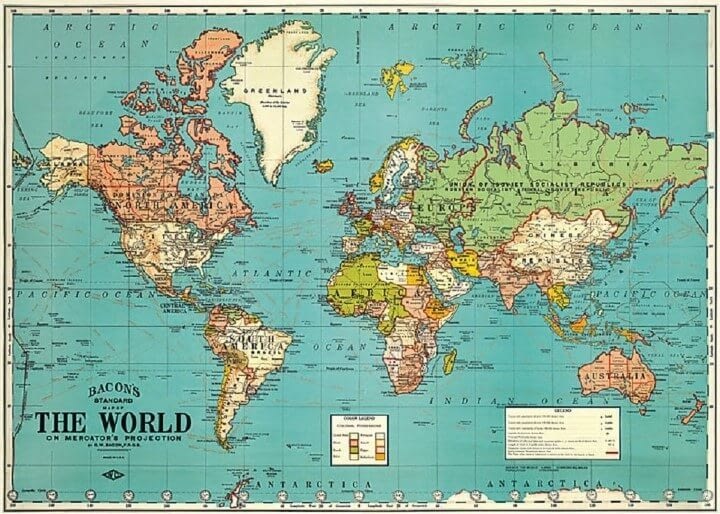

In the 19th and 20th century, as the number of mariners grew, so did the prevalence of Mercator projection maps. Anyone who has visited a Western classroom in the last half-century is familiar with this projection. The trouble is, its inaccuracies bolster attitudes of ethnocentrism, the belief in the inherent superiority of one’s own ethnic group or culture, and even unconsciously racist worldviews. The Mercator projection maps tend to emphasize European and Northern societies; in a typical version, the countries above the equator take up close to ⅔ of the page space, diminishing the importance of Southern continents and nations (whose populations are largely people of color). Jane Elliot has famously spoken about the distortion of the Mercator Projection and stated “This is not just ridiculous, it’s deliberate”. Greenland’s size in relation to South America is a good example here. In the age of colonialism, this presentation of European nations helped underscore their ideas of superiority over other nations.

Mercator Projection, via brilliantmaps.com.

As proof that the long term use of Mercator projection maps may have less to do with accuracy and more with biased attitudes: when the Soviets undertook their ambitious world mapping endeavor, they used the Pulkovo 1942 projection.

In recent years, educators and mapping companies have worked to rectify this situation. Companies like ODT Maps are working to correct the distortion caused by longtime use of Mercator maps by distributing maps like the one developed by Arno Peters in 1974 map, which aims to be fair to all people.

As ODT Maps founder Bob Abramms says in a lecture, “for a map to show the truth, it must make a visual lie of something else”. A globe sliced apart and laid flat, for example, is not easily decipherable to a layperson. The Mercator projection shows accurate lines of passage but distorts continent proportions. Today, digital geospatial technology allows users to parse data in three dimensions, meaning fewer of these trade-offs, but it’s import to keep historical misleading cartography in mind and ensure any distortions are clearly communicated and not presented as fact.

The Evolution of Cartography

It may sound hyperbolic, but history proves that when maps change, so does humanity’s perception of itself.

Just as Cold War-era maps by the Soviet Union reflect certain ideas about that society’s worldview, so do maps left by ancient civilizations. A clay tablet from around 600 BCE called the “Babylonian Map of the World,” is thought to be among the first-ever known maps. It features Babylon in the center of the known world surrounded by water and eight triangular regions. This arrangement is thought to be a symbolic, rather than literal, representation of the world. Older maps from Greece are organized similarly.

(The Babylonian Map of the World. Known as the first map ever created. Image courtesy of Ancient History Encyclopedia.)

Around 150 BCE, Greek mathematician and geographer Ptolemy created his atlas, “Geographia.” This work is a cartographic milestone, as, while working to establish a grid that would more accurately chart birth locations for horoscopes, Ptolmey created a global coordinate system that laid groundwork for our modern system of longitude and latitude.

Ptolmey’s work had massive influence on medieval Islamic scholars. In 1154, one of those scholars, Muhammad al-Idrisi, created the most accurate map for its time. The Tabula Rogeriana. Al-Idrisi’s achievement combined Ptolmey’s system with knowledge of the Far East, Africa, and the Indian Ocean gathered by explorers and merchants.

Information from explorers and merchants continued to play a crucial part in map-making, as the 15th century saw an explosion of exploration. One of the most significant innovations from this period is Gerard Mercator’s 1569 World Map, which used a cylindrical map projection to effectively ‘flatten’ the globe for nautical travel.

(Gerard Mercator’s 1569 World Map. Image courtesy of ClassicSailor.)

Tools like telescopes, compasses, and sextants allowed for increased accuracy. These tools of surveying were put to good use on land, too. In 1912, Alfred Wegener used surveying tools to add proof to the theory of continental drift, which was eventually accepted half a century later.

The invention of the printing press pushed maps into the hands of more people than ever before. Following the Industrial Revolution, as middle classes rose and more people found more free time in their days, a spike in travelling as a hobby occurred. Map makers found demand shifting from ornate, often symbolic maps, to ones of a more utilitarian nature for use by common travelers.

World War I introduced aerial photography, which progressed through the following century into today’s world of satellite imagery, remote sensing, and LiDAR.

One of the biggest revolutions in the field was the ability to pick and choose what data to include on a given image. The first Geographic Information System (GIS) was created in Canada in 1962 by Roger Tomlinson and the Canada Land Inventory (CLI). This allowed for separation of information and attribute data, meaning more specialized visualizations. In 1973, first editions of large digitized maps made their entrance into the cartographic landscape.

(Image courtesy of ArcGIS.)

Throughout the centuries of progress, one thing remains true: maps are an abstraction of reality with some elements depicted more prominently than others. Today, as it was in the past, the cartographer’s job is to make sure it is done the most effective way possible.

Relief shading, which adds depth and dimension to maps, is just as important today as it was in the 17th century. Today, cartographers might use ESRI Toolsets instead of an ink pen, but the idea is the same. Modern cartographers make choices that help viewers of their maps understand climate change, shipping routes, special-interest hiking trails, and even make maps more accessible to individuals with color-blindness.

At East View Geospatial, our cartographic team is as busy as it has ever been, utilizing the latest and greatest mapping tools. Most recently, the team identified a gap in country map coverage for the country of Tanzania at 50K scale. Utilizing data from the Tanzania government and Maxar, as well as toolsets from ESRI, the cartographic team created 16 new map sheets, completing Tanzania’s map coverage for the first time in history. This entire project was executed remotely, without any EVG personnel having boots on the ground in Tanzania. The entire project would not have been possible without innovation in the cartographic space over the past centuries. To see how this project was executed, EVG created a brief StoryMap that breaks down the process. As a company, we are constantly pushing the boundaries to find new ways of sourcing data and executing the cartographic production process to bring the most authoritative maps to market.

The Rich History of Soviet Mapping

A Soviet map of Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, California.

Following World War II, the Soviet Union set out to map the entire world. The full story of how they did this remains untold, but the legacy of the maps they produced is clear; they are potentially the pinnacle of pre-satellite-era cartography, rich in both aesthetics and diverse data.

Scholars and researchers have used the maps to gain perspective of the USSR worldview. Some argue that the combination of topography with human infrastructure represents an attempt to synthesize the two and express a post-revolutionary worldview. From a more practical standpoint, the map’s content points to potential objectives; from invading (or defending) to understanding.

The maps feature topographic and geographic features, but the amount of auxiliary information they contain is astonishing. Widths of streets, sizes of buildings, and even construction materials and conditions of roadways are recorded in cities around the world. In mountainous regions like Afghanistan, maps include notes on times of year when snow clears from mountain passes. In other areas, maps note where to find edible vegetation and drinkable water. Some even feature the inclusion of military and research facilities that do not appear on official maps from the surveyed country.

In 2005, East View, which has assembled the world’s largest single collection of these maps, translated and published a Russian military manual that provides instructions for how the maps are to be used in planning and executing operations. Tables in the manual provide even more detailed information, like how far certain sounds travel in a given area, even accounting for what kind of material the sound was made on: everything from an idling tank to footsteps to a snapped tree branch.

A Soviet map of the Pentagon in Washington, D.C.

Some of the Soviets’ quest for granular detail in their maps must have come from their military strengths. While the United States Air Force maintained air superiority, Russian forces relied on tank and ground forces. While the Americans were able to formulate a strategy from the sky, the Soviets needed maps that allowed them to plan for more precise ground operations. Typically, 1:50,000 is an ideal scale for such activity.

The Soviet military’s mapping of worldwide urban centers was unparalleled until the arrival of Google Maps. Thousands of cities are mapped at scale 1:10,000 and 1:25,000 – and comprehensively so, not just potential military targets. The detailed mapping of cities like Washington, DC, New York, San Francisco and Seattle are perhaps expected by an adversary. But Pueblo, CO, Madison, WI and Shreveport, LA – points to an obsession within cataloging and measuring American postwar industry and business strength.

The maps were made using a combination of existing official sources (similarities to maps produced by the Ordnance Survey and by US Geological Survey are too numerous to be coincidental), on-the-ground surveyors, reconnaissance aerial photography, and, presumably, spies. Teams were sent out to some of the furthest corners of the earth in pursuit of cartographic knowledge, and some died in their pursuit. Russian cartographer Alexy Postnikov, who, when on assignment to survey a remote area of Yakutiya in the 1960s, found an inscription left by an ill-fated cartographer from 1948. It was left 200 km away from the nearest populated area and stated that he and an injured aide were alone without supplies and fending off bear attacks.

A 1980 Soviet map of San Diego naval facilities (left) compared with a US Geological Survey map of the same area, from 1978 (revised from 1967).

Regardless of the maps’ purpose, it is clear the Soviet government regarded them as precious. Access to them was highly restricted. A strict system of checking out the maps existed, and ex-military members describe feeling that, even if it had been partially or totally destroyed, whatever pieces remained needed to be returned.

When the Soviet Union fell and laws changed, officials and others with access to them started marketing the maps bit by bit to a scattered constellation of buyers, which is how the world knows about them today.

“What remains most impressive about the Soviet maps was their uptake and utilization by industries far and wide – both commercial and consumer”, notes Jonathan Thompson, Director of Sales & Marketing for East View Geospatial. “From telecom and utility to aviation and insurance companies, as well as recreationists and historians alike, these maps have been and continue to be highly regarded and used for countless applications. In fact, for some regions of the world, they still represent the highest quality published topographic information.”

More information about the maps is available in The Red Atlas, a book by John Davies and Alexander J. Kent, which gives an in-depth history of their creation and use. We also recommend reading “Inside The Secret World of Russia’s Cold War Mapmakers” by Wired. East View had the opportunity to contribute their knowledge of Soviet mapping in both The Red Atlas and the Wired article.

For those wanting to dive into the depths of these maps, East View Geospatial’s MapVault service provides access to our vast collection of Soviet mapping as a web mapping service. Each map is available individually in a variety of print and digital formats at shop.geospatial.com.

As cartography continues its march into the future with computer and satellite-aided tools, the painstaking efforts of those Soviet topographers, surveyors, and others will continue to provide an example of outstanding tradecraft whose relevance and value continue to find new applications.